Caring for Our Ancestors

“The past is never dead. It isn’t even past,” wrote William Faulkner in 1951. But, for Shana (Bushyhead) Condill '99 and her profession, as the director of the Museum of the Cherokee Indian and a member of the Eastern Band Cherokee nation, the past is alive, and it is living with purpose.

One of Shana’s first projects since joining the Museum of the Cherokee Indian in 2021 has been overseeing the process of removing from display items that are sacred or funerary. For now, these items are being replaced with contemporary works of art created by Cherokee artists while the museum, and the tribe as a whole, decide where they should go.

“It’s going to take years,” Shana said, but the project is attempting to answer a question that is emerging at the heart of Native American identity in the 21st century.

“For generations, being able to study things like history and archeology and anthropology wasn’t possible for Native people, and, even when it became possible, these were disciplines that Native people distrusted because the archeologists and anthropologists were the ones who took our history from us and disrespected it,” Shana said. “But now we’re starting to enter those fields and answer the question, ‘How do you run a museum for a living culture?’”

· · ·

Shana was born in Montana, but her dad worked “all over Indian country,” first as a substance abuse counselor and later working for the United Methodist Church serving Native communities, bringing the family along with him to Oklahoma and Wisconsin. From her high school in Milwaukee, Shana was convinced to apply to Illinois Wesleyan by her alumnus pastor and decided to attend after an overnight visit to campus.

She came to IWU as a chemistry major interested in a career in environmental chemistry, but that didn’t last the first semester.

“I was kind of a weird overachiever in high school doing band and sports and everything, and I came to Wesleyan thinking I would do the same thing,” so she immediately dove into chemistry, physics and calculus, which she flunked. Her first-semester GPA was 1.5.

But she was also taking a women’s history course as a “fun class,” until she realized that it didn’t just have to be for fun. It could be a career path. She ended up becoming a double major in English and history, with an enduring fondness for Professors Dan Terkla, Tom Lutze and April Schultz.

It was Terkla, now a professor emeritus of English, who turned her interest toward museums when he invited a scholar from the National Museum of the American Indian to speak on campus and encouraged Shana to attend.

“I was sitting in this lecture having my mind blown,” Shana remembers. “To hear her talk about a museum specifically for Native people, I was floored.”

Guided by Schultz, Shana interned at the Museum of the Cherokee Indian and the National Museum of the American Indian. On campus she completed an honors project on IWU’s John Wesley Powell collection of Southwestern pottery as a case study of Native representation in museums.

“He was the director of the Bureau of Ethnology at the Smithsonian, so I see John Wesley Powell’s name everywhere I go,” Shana said. “It’s kind of funny to start at a little Midwestern school working with his collection and have him follow me throughout my career.”

Still, “At that time very few universities, let alone a little one like Wesleyan, had a Native studies program, so building my own is something all my professors helped with,” Shana said. “And I spent the rest of my time at Wesleyan trying to make up for that 1.5.”

· · ·

Shana met her husband, Buck Condill '99, in one of Lutze’s classes during their senior year, and the two married when they moved for Shana’s master's education at the University of Delaware. But the beginning of her career brought her back to Illinois where her husband’s family, for six generations, had and still owns a farm-turned-historical tourism business in Arthur, Illinois.

Between her short stint as a curator at a small Pennsylvania museum and over a decade at her husband’s family business, Shana was wearing every hat there was in directing an organization, even though she told herself in graduate school that she would never be a museum director. Shana wanted to be in the trenches, and when she was offered a job with the National Gallery of Art on Washington D.C.’s National Mall, she was ready to go back in.

But the experience was, at first, not what she expected.

“I got there and I thought, ‘Woah, this is pretty old-school’” Shana said. “It was based on a European idea of museums,” and its collection in 2017 was especially dismal in Native American representation. There were only 24 total pieces from Native artists, all of which were works on paper — pieces rarely able to be displayed publicly due to their sensitivity to light. Shana worried that she had made a mistake, until the museum’s director retired, and his replacement was Shana’s dream pick.

Kaywin Feldman, a leader in reimagining museums in an era of their decolonization and increased self-representation of American cultures, became the new director. Shana was ecstatic, especially when Feldman lived up to her expectations by acquiring a piece by the contemporary artist Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, a citizen of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Nation.

Feldman became a role model for Shana, exemplifying what it could mean to be a director that moved a museum forward, not only by expanding a diverse collection from the past but the present as well, and she decided that she had to stay. And she did stay, until she had no choice but to leave.

· · ·

“It looks like we’re moving to North Carolina,” Shana’s husband said as he tossed a copy of The Cherokee One Feather newspaper at her. The Museum of the Cherokee Indian, nestled in the Great Smoky Mountains about 40 miles west of Asheville where Shana had interned as an Illinois Wesleyan student, was looking for a new director. But deciding to apply wasn’t a given.

“I had a sense of responsibility to my tribe, that I wanted to make sure that the person who got this job was the best person for the job,” Shana said, and she had never wanted to be a director herself. But the sense of responsibility overwhelmed her to the point that whatever she wanted personally became indistinguishable from what she wanted for the tribe. If she applied, she could help the museum find the best person for the job, and they decided it was her.

In taking the job, Shana would be splitting her time between D.C. and North Carolina while her daughter was still in high school back at the capital, but she would return to the conversation that she had first entered with her honors project at Illinois Wesleyan.

“We’re rethinking what it is to tell a story of a living culture,” Shana said. A museum by and for the Cherokee people is in a unique position to lead that conversation, and it wasn’t long before Shana was overseeing the project that would attempt to provide an answer.

· · ·

To Shana, the museum and the Cherokee people, the objects on display are not inert, inanimate things.

“We believe that, when someone makes something — a tool, a bowl, a piece of art — they are putting a part of themselves into it. They’re giving it life,” Shana said.

It’s even preferable to not call, or think of, the items in the museum’s collection as “objects” but as “ancestors.” They are a remaining piece of the person who made them that is imbued with that person’s life and purpose and is on a continuing journey. Shana only calls them “objects” to distinguish them from the bodily remains of tribal ancestors, begrudging the fact that English lacks a word for what the objects are.

And the living purpose of many, if not all, of these objects may not be as exhibits in a museum or even items in a collection. Certainly in the case of funerary objects, they have an originally intended place and purpose that still exists, the same as a stone over a grave in a cemetery, but they have been taken from that place by people who likely didn’t understand or respect their purpose. Their journey has been disrupted.

“Disruption” is the theme, and the name, of the new exhibit that is making this point at the Museum of the Cherokee Indian. Shana, along with the museum staff and board, decided to remove 122 objects from display, out of more than 500 total, until they can be reviewed.

Doing so is a scholarly exercise, determining the facts of an artifact's history, but it is also a spiritual one. The ultimate decision to be made is where the object is in its journey and where it should go next.

But the emptied display cases are also an opportunity for new objects with new journeys, because, as Shana wants visitors to know, “We aren’t still in the 1800s living in teepees. There are tons of Cherokee living today, creating a living culture that we can exhibit.”

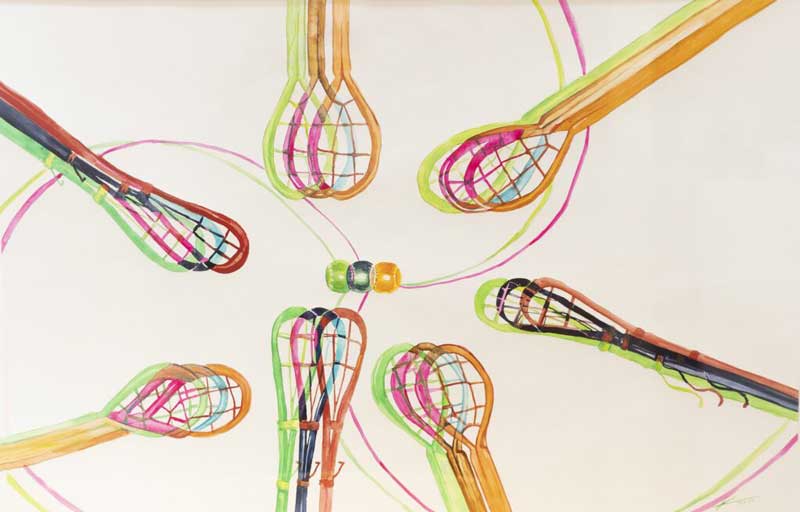

So the removed objects have been replaced, for the time being, by newly made art that is conspicuously modern. It features fresh, bright colors — contrasting with the expected earth-tone exhibit, even “disrupting” it — with contemporary styles and artistic tools, including Sharpie markers. They exhibit modern Cherokee culture just as prominently as the previous objects exhibit ancestral Cherokee culture, but, crucially, the purpose and journey of these objects intentionally placed them in their displays.

In the meantime, the question of which and whether the ancestral objects should remain in the museum’s collection or returned to their original purpose is not straightforward, and there is immense weight in the decision.

The person who made an object might have intended it for a specific ceremony their people would perform, yes, but they didn’t know that there would be centuries of colonization and genocide of the people they made it for.

“If they were alive today, would they want its new purpose to be to teach their descendants about Cherokee history?” Shana asked.

The ancestors who made these objects can’t answer, which makes the duty that falls to Shana, the museum and the Cherokee people deeply humbling as they care for their elders who suffered generations of injustice — and the same elders care for them by continuing to serve the purposes they fulfilled in their creations.

“It’s a world of high highs and low lows,” Shana said. But the Disruption exhibit is the culmination of her own career’s purpose so far.