Life of Crime

Associate Professor Amanda Vicary, who brings true crime into her psychology courses at Illinois Wesleyan, has become a highly sought-after expert in the crime community.

Story by Matt Wing

Did you binge watch Making a Murderer ? Did you listen to Serial ?

Do you have a secret true crime obsession?

Amanda Vicary does, too.

But while most of us grapple over innocence or guilt in the true crime we consume, the Illinois Wesleyan psychology professor asks a deeper question.

Why are we so interested in this?

A self-described “true crime addict,” Vicary also weighs innocence and guilt in the true crime books she devours. But she’s even more interested in the psychology behind crime, at play in the justice system and in prison life, and our interest in all of it.

And Vicary has found a way to fuse those interests with her academic expertise.

True crime frequently plas a role in the psychology courses she teaches at IWU, including a First-Year Experience centered on wrongful convictions that she’s leading for the first time in 2019-20.

Furthermore, she’s become a crime psychology expert who is regularly sought out to provide analysis for leading publications, podcasts and television programs.

“I never thought that I’d find a way to incorporate my obsession with crime into my professional life,” Vicary said. “Sometimes I’ll be reading through court documents or watching Dateline and think, ‘I can’t believe I’m actually working right now!’”

•••

Vicary can trace her interest in crime back to a singular moment from her childhood growing up in tiny Hanna City, Illinois (pop. 1,013).

“My mom has always been a big true crime fan, and I remember she gave me a book called The Woodchipper

Murder ,” Vicary recalls. “I was pretty young, so this was definitely questionable parenting, but I read it and I was hooked.”

Reading true crime books became a source of mother-daughter bonding. It continued as a hobby throughout her formative years. She never considered it anything more than that.

Vicary eventually found her way to Bradley University in nearby Peoria, Illinois, where she planned to pursue a degree in journalism. She changed her major to business management. And then psychology.

“I turned in a paper for an experimental psychology class where I had to create a study, and my professor told me he thought I could actually carry out the study if I wanted,” Vicary recalls. “It was on attraction and eyeglasses and eyesight, so I carried out the study and I loved it.

“That changed the course of my life.”

Vicary left Bradley with a bachelor’s degree and headed for the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, where she began pursuit of a doctorate. She studied social psychology with a focus on romantic relationships. She spent years examining attachment theory and its impact on adult relationships.

Meanwhile, Vicary’s interest in crime persisted as she built an impressive personal library of true crime books. She developed favorite authors, favorite topics — even favorite cases of serial killers.

Finally, one day while speaking with her academic adviser, she came clean.

“I just told him I was really into this crime stuff,” Vicary remembers. “It was totally outside his realm of interest, but I told him how I really liked to read about crime, and how my mom was really into learning about crime, and he said that his wife was really interested in crime.

“And then it hit me: is it only women who are into crime? ”

The hypothesis gave way to a study that mostly confirmed her prediction. Women are indeed more likely to develop an interest in true crime, Vicary found, just as they are more likely to fear becoming a victim of crime. Desire to understand how one becomes a victim and to know how violent crimes are perpetrated, and to learn techniques to avoid and survive violent crimes, were identified as the main reasons women are drawn to true crime.

“In reading these stories or listening to these podcasts, you learn how people get murdered, how people get kidnapped. You learn techniques to survive, even if they are as simple as locking your door,” Vicary said. “Anyone who knows me can tell you that I’m completely paranoid — I have all these little devices around my house and my husband thinks I’m a total nutcase — but I think learning the survival skills may be why I like crime as well.

“Consciously or unconsciously, when you read these books or watch these shows, you’re learning what to do if it happens to you.”

Vicary’s study on true crime interest veered sharply from her previous study in romantic relationships, yet she found a way to connect the two in her dissertation, which examined women’s attraction to serial killers.

But she soon found herself at the proverbial fork in the road: would she focus her career as a psychologist specializing in romantic relationships or would she choose to pursue her passion for crime psychology?

She chose a life of crime.

“I thought that wherever I went, that’s what I wanted to do and what I wanted to teach, and that’s what I wanted to talk about,” Vicary said. “I came to Illinois Wesleyan and presented my true crime research, and fortunately the psychology department liked it enough to offer me a job.”

•••

Vicary asks her PSYC359 class what they know about the O.J. Simpson case.

She’s astounded by the responses.

The students enrolled in Vicary’s social psychology course know Simpson is an ex-football star and most are aware of a bloody glove as a key piece of evidence. One says he knows something about a car chase with a Ford Mustang.

Vicary reminds herself these students weren’t yet born when Simpson was tried and acquitted of double murder. She politely corrects the student, who has misidentified the vehicle in the infamous car chase that played out live on national television. It was a Ford Bronco .

Students will read Without a Doubt by Marcia Clark, the lead prosecutor in the Simpson trial. They’ll be provided an understanding of the justice system through the lens of the “Trial of the Century.”

“The students love it,” Vicary says. “They’re so excited about it even though it happened so long ago.”

Crime plays a part in nearly every course Vicary teaches, though sometimes only tangentially. But crime and the justice system are at the forefront of the First-Year Experience she is leading in 2019-20. First-year students enrolled as “Justice Scholars” will learn how and why people are wrongfully convicted and explore local cases that are currently being represented by innocence projects.

Students will examine the evidence against Barton McNeil, convicted of the 1998 murder of his 3-year-old daughter, and Jamie Snow, convicted of the 1991 murder of a gas station attendant during an apparent robbery. Both murders took place near Illinois Wesleyan’s campus, and McNeil is the son of a former IWU art professor (also named Barton McNeil).

“Several big local cases have been overturned and these are two cases that have received a lot of attention with podcasts and innocence projects working on their behalf,” Vicary said.

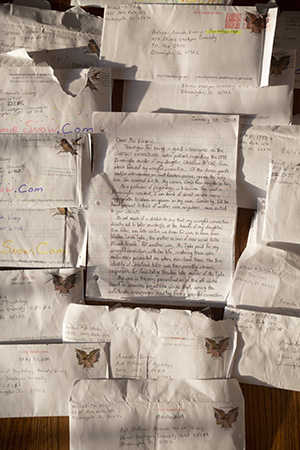

Students will read courtroom transcripts, speak with attorneys and correspond with the men convicted of the murders. They’ll also tour the local county jail and juvenile detention center, and attend The Innocence Network’s annual conference, in March 2020, in Chicago.

“My goal for the class is that students will have a really immersive, engaging experience,” Vicary said. “The hope is that this type of teaching will help bring the material to life and help students see how what they’re learning is relevant to their community and social justice more broadly.

“What better way to understand the impact of eyewitness testimony than to talk to a prisoner who was convicted because of it?”

•••

Vicary found an audience in the crime community through her study of women’s interest in true crime. But her presence continues to grow as she conducts more research, often with the aid of IWU students.

In addition to her study of women’s attraction to serial killers, she’s studying true crime podcasts and their appeal to both women and men. She previously studied the social media activity of students in the aftermath of school shootings. She’s looked at veterans who have committed crimes and public attitudes toward them.

Vicary also continues to research wrongful convictions and the implications of eyewitness testimony, false confessions and faulty forensics. She’s become especially interested in analyzing camera angles used to capture confessions and how jurors can be influenced by the seemingly unimportant placement of interrogation room cameras.

Vicary has also studied the so-called “CSI Effect,” which asserts that, due to the proliferation of television programs centered on crime and forensic evidence, jurors’ expectations of the prosecution are higher than ever before. Some speculate the CSI Effect has produced more informed criminals who commit crimes more stealthily, leaving behind little or no evidence.

A student researcher assisted Vicary in a study of the CSI Effect. They polled over 300 students on the steps they’d take to avoid detection if they were to break into a home. “Some of the students were expert criminals!” Vicary said, still in disbelief. “Some thought of things I’d never even considered.”

Students were also asked which TV shows they watched, and a majority of the students who said they’d wear gloves or drive a different car while committing the hypothetical crime admitted they were really interested in shows like CSI and Law & Order . “It was that forensic knowledge they had learned from watching those shows,” Vicary explained.

But while she marvels at her students’ expertise, Vicary has herself become an expert in the crime community, often called upon to provide analysis in the true crime genre she became such a fan of growing up.

Vicary has appeared on an episode of Investigation Discovery’s Married with Secrets, which detailed the investigation into a Bloomington police officer for a string of rapes, for which he was sentenced to 440 years in prison, one of the longest sentences handed out in state history. She’s offered commentary in articles published in wide-ranging publications, from GQ to Forbes . From The Indianapolis Star to The Louisville Eccentric Observer . She’s been featured on radio programs originating from faraway places like Colombia and Sweden.

And she appeared on the podcast Suspect Convictions where she offered insight into the Barton McNeil case.

Shortly after the episode was released, Vicary received a letter from McNeil. She wrote back, and they now communicate on a weekly basis. They talk about his case, but discuss other topics as well. Vicary has goaded McNeil into watching The Bachelor , which they often recap in their weekly correspondence.

“I like him a lot. He’s a funny guy,” Vicary said of McNeil, the first incarcerated person she’s ever communicated

with. “I think he’s so desperate for someone to talk to that he’s willing to talk to me about The Bachelor .”

The interaction with McNeil has given Vicary the confidence to reach out to others living in the corrections system. She corresponds with Jamie Snow and his family, and has visited him at Stateville Correctional Center in Joliet, Illinois. She’s interviewed over 50 women about their relationships with incarcerated men, including Snow’s girlfriend. (For the record, Vicary is happily married to a man outside the corrections system. Together they have a 2-year-old son.)

Vicary’s research continues. So does public interest and media demand for her as an expert. And though she’s always expecting a wane in that interest and the demand for her views, it hasn’t come yet.

“I always think that true crime has reached the peak,” she says. “But then two or three more journalists will call. A new true crime podcast will come out. There will be a new show on Netflix.

“It just seems to keep going.”

So does her passion for teaching and incorporating crime into the psychology courses she teaches at Illinois Wesleyan.

“I love this school. They hired me knowing I was going to do offbeat research and study offbeat things, and I continue to do so,” Vicary said. “And I love my colleagues in the psych department and others here who are so supportive of what I do.”