An Ocean of Opportunity

By Matt Wing

The classroom Jamie Blumberg ’19 reported to each morning for a week last August was unlike other educational settings. No desks. No blackboards. No walls.

This was no typical classroom.

Warmed by the late summer sunshine and with a coastal breeze filling her nose with a smell most people associate with the ocean (most times it’s actually seaweed they are smelling), Blumberg’s college campus this week was the Smithsonian Marine Station (SMS) at Fort Pierce, Florida.

Her classroom? The Atlantic Ocean.

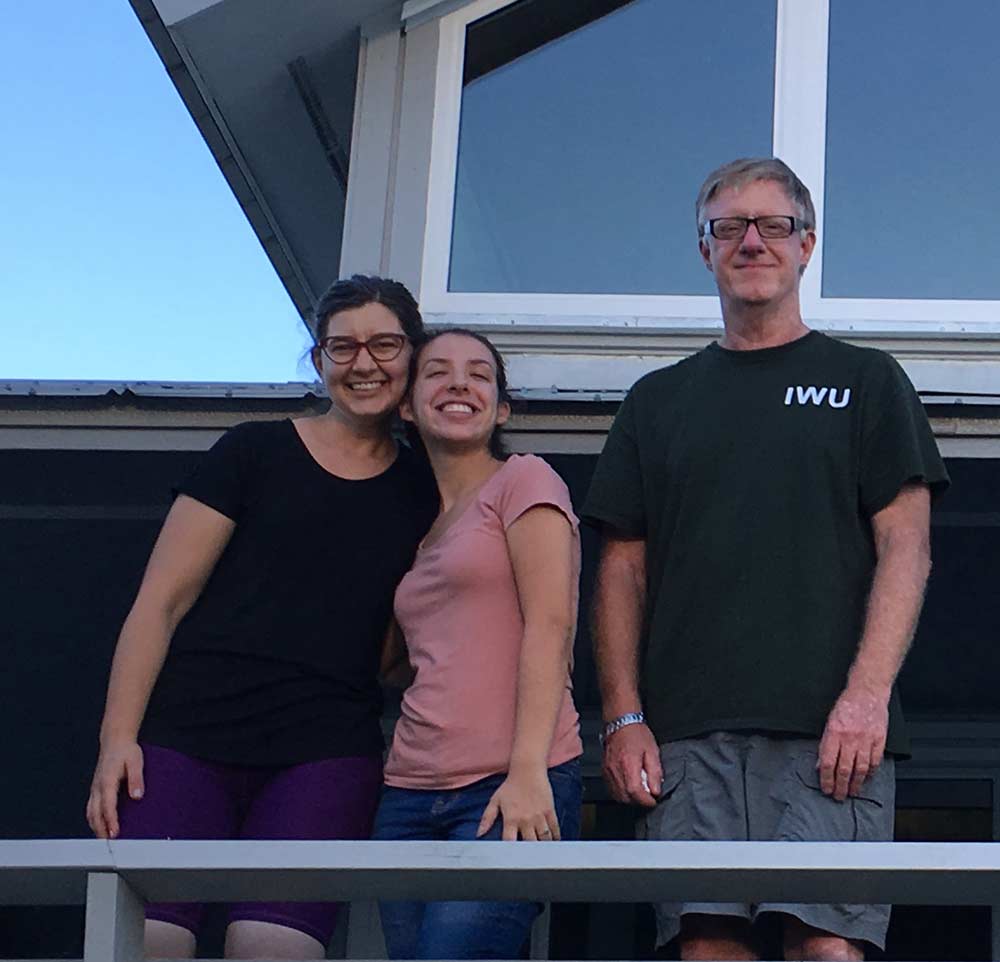

Joined by IWU Professor of Biology Will Jaeckle, Blumberg was on her second of three such research trips to the SMS. The IWU contingent had flown to Florida’s Atlantic Coast to take part in STREAMCODE, a joint project of the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History’s Department of Invertebrate Zoology and the Smithsonian Marine Station’s Life Histories Program. A talented group of researchers, with wide-ranging expertise, had converged on the SMS to study the diversity of life in the Gulf Stream.

All three of Blumberg’s SMS expeditions have provided immersive marine research experiences, in many ways embodying what the University has come to call a Signature Experience – a capstone project encompassing the totality of a student’s IWU education.

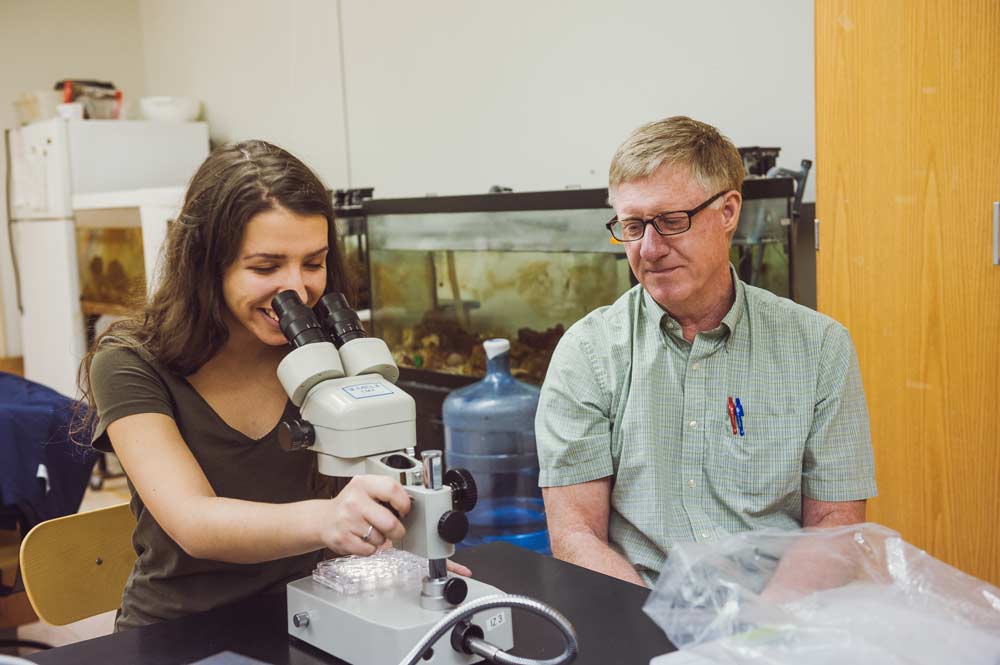

“You learn a lot of good things in the classroom, but it’s very different to be hands-on and to be experiencing those things and seeing them through a microscope yourself,” Blumberg said. “It’s a very valuable learning experience when you’re at the SMS.”

Jaeckle has been studying planktonic invertebrates at the SMS since the early 1990s. With its direct access to the Atlantic Ocean and Indian River Lagoon, first-class research facilities and convenient on-site living quarters for visiting researchers, the SMS is an ideal spot to take students.

And like an expert angler who knows all the best fishing holes, Jaeckle knows just when and where to go to begin the collection of samples. He’s taken students to the Bahamas and done field research in Antarctica, but the SMS offers a prime location for faculty-student research.

“I have a pretty good sense of which animals will be available and how to get the specimens we need, so it’s a place where I feel really comfortable, in terms of being able to get the materials that the students need to do their work,” he said. “There are a great number of uncertainties that are eliminated by working at the SMS. It’s an easy place to work, the animals are really nice, and I know it really well. It’s a safe place for me to take students.”

Though the focus of each expedition varies, the processes of collecting, examining and cataloging remain constant. And every time a net is cast into the ocean or one peers through a microscope, the potential for discovery is very real. That’s why Jaeckle, Blumberg and other scientists return to the SMS each year to continue their research.

“Even for me after all these years, there’s the possibility of seeing something new,” Jaeckle said. “There’s the possibility of learning something new.”

That type of curiosity helped steer Blumberg into the sciences. She started her college journey at the University of Alabama, where she worked in a laboratory studying mutant strains of yeast as a model for cancer cells and looking at various mutants’ resistance to cancer drugs. But Blumberg, who was home-schooled from the second grade through high school, grew increasingly homesick during her first year. She also wasn’t being challenged academically. Earning an A+ in honors biology seemed far too easy.

Transferring home to Illinois Wesleyan University was an easy decision.

And if there was any doubt she had made the right decision, it was quelled when she met Jaeckle.

“On the first day he asked me what I was interested in, and I told him I was interested in viruses,” Blumberg recalled of her first exchange with the IWU professor. “He was like, ‘Oh, I’ve got something for you!’”

Blumberg and Jaeckle devised a research topic that combined her interest in viruses with his interest in invertebrate animals. But beyond the development of the topic, Blumberg has taken total ownership of the ongoing research.

Blumberg’s attention to detail has helped produce clean results as she asks and answers questions through experimentation. Also aiding in the process is her genuine sense of curiosity. Like her professor, she enjoys the thrill of the hunt.

“She is curious,” Jaeckle said. “And she seems to enjoy the process as much as the results of that process.”

It helps if a scientific researcher can enjoy the journey as much as the destination. Individuals don’t make groundbreaking discoveries every day, so being able to enjoy the day-to-day work is essential.

But one day last year while Blumberg was conducting research in an on-campus lab, she noticed something interesting when she looked at a specimen through her microscope. She quickly called Jaeckle over to confirm her finding.

“He said, ‘Jamie Blumberg, you are the only one in the world right now who knows that this unicellular organism ingests viruses,’” Blumberg said, recalling the breakthrough moment. “That discovery was something I learned that I could share with the rest of the world.”

That sharing of new information with the scientific community and the interconnectedness of the discipline are reasons why people like Blumberg and Jaeckle are drawn to science. Each discovery helps us better understand the world we live in and, in turn, holds the potential to inspire future discoveries.

This cycle is perhaps best explained using Jaeckle’s analogy where each discovery is a brick.

“So we are all adding bricks, but the question then is: does it make a wall, or is it just a pile of bricks?” Jaeckle posed. “Each one represents a discovery, but what is important is how all the individual bricks come together to create a whole.”

The research Blumberg and company conducted during STREAMCODE, and in other research trips to the SMS, is an attempt not only to produce more bricks, but to organize those bricks into a structure, something with a sum greater than its parts.

Bringing together scientists with varying areas of expertise is vital for projects like STREAMCODE. Having Blumberg and Jaeckle, and their experience in identifying invertebrate larvae, and a host of others ranking as authorities in very specific fields, are what make projects like STREAMCODE work.

“There are so many people who have dedicated their lives to study so many different things, and when you get them together you’re amazed that someone could tell you exactly what jellyfish you’re looking at when everything looks the same,” Blumberg said. “All you can hope for is that someday you’re the person to share a piece of that puzzle for someone else.

“And that’s what I loved about those trips.”

Among the experts on hand to take part in STREAMCODE was a scientist who was once in Blumberg’s shoes. In a “small world” moment, Blumberg and Jaeckle worked alongside Stephanie Bush ’02, an IWU alum and former biology major who has gone on to study invertebrates, with an emphasis in cephalopods.

When she scanned the list of STREAMCODE attendees in an email detailing the project, she was elated to see a name she recognized.

“I was like, ‘Oh my gosh, Will Jaeckle!’” Bush remembers thinking.

Though she hadn’t been taught by Jaeckle at Illinois Wesleyan, Bush had been acquainted with the professor. She had a similar experience to Blumberg, having worked closely with the late professor Susie Balser, who helped steer her toward a study abroad opportunity in Australia and a May Term marine biology course that included travel to the Great Barrier Reef.

Balser later tipped Bush off to an internship at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute, where Bush eventually earned a full-time position. She is now a member of the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History Invertebrate Zoology Staff.

While working with Jaeckle and Blumberg, Bush saw a little bit of herself in Blumberg.

And Blumberg saw a little bit of herself in Bush.

“I could tell immediately she was a hard worker and she was always enthusiastic,” Bush said. “It was really great to have her there.”

Blumberg said her experience working with Bush helped her see the real-life steps to advance from an undergraduate to graduate school to an internship to a full-time job as a working scientist.

“Working with her was great because you could see what happens after you graduate from IWU. She went on to grad school, she’s traveled the world on her different expeditions, and she’s so knowledgeable in her field,” Blumberg said. “STREAMCODE was just us sorting everything we could find, and so if I found something and I didn’t know what it was, and it was something Stephanie worked with, she was able to identify it and show me what it was, and that was very helpful.”

Blumberg isn’t quite sure what her next step will be after she graduates in December 2018. She got married over the summer and, after she graduates, is planning to work in a lab in Peoria, Illinois. Grad school will most likely follow.

What comes after that is up in the air, but whatever it is, Blumberg thinks she’ll be ready.

“I feel really prepared, especially for grad school or whatever I’m going to do afterward, even if it’s just working in a lab, because I’ve been really challenged here at IWU,” she said. “I’ve also been given the opportunity to develop skills that I can use to solve problems on my own, and I can think critically about things, design experiments and implement them.

“I feel more confident and independent since coming here, and I think that has a lot to do with the environment that I’ve been working in since I got to IWU.”